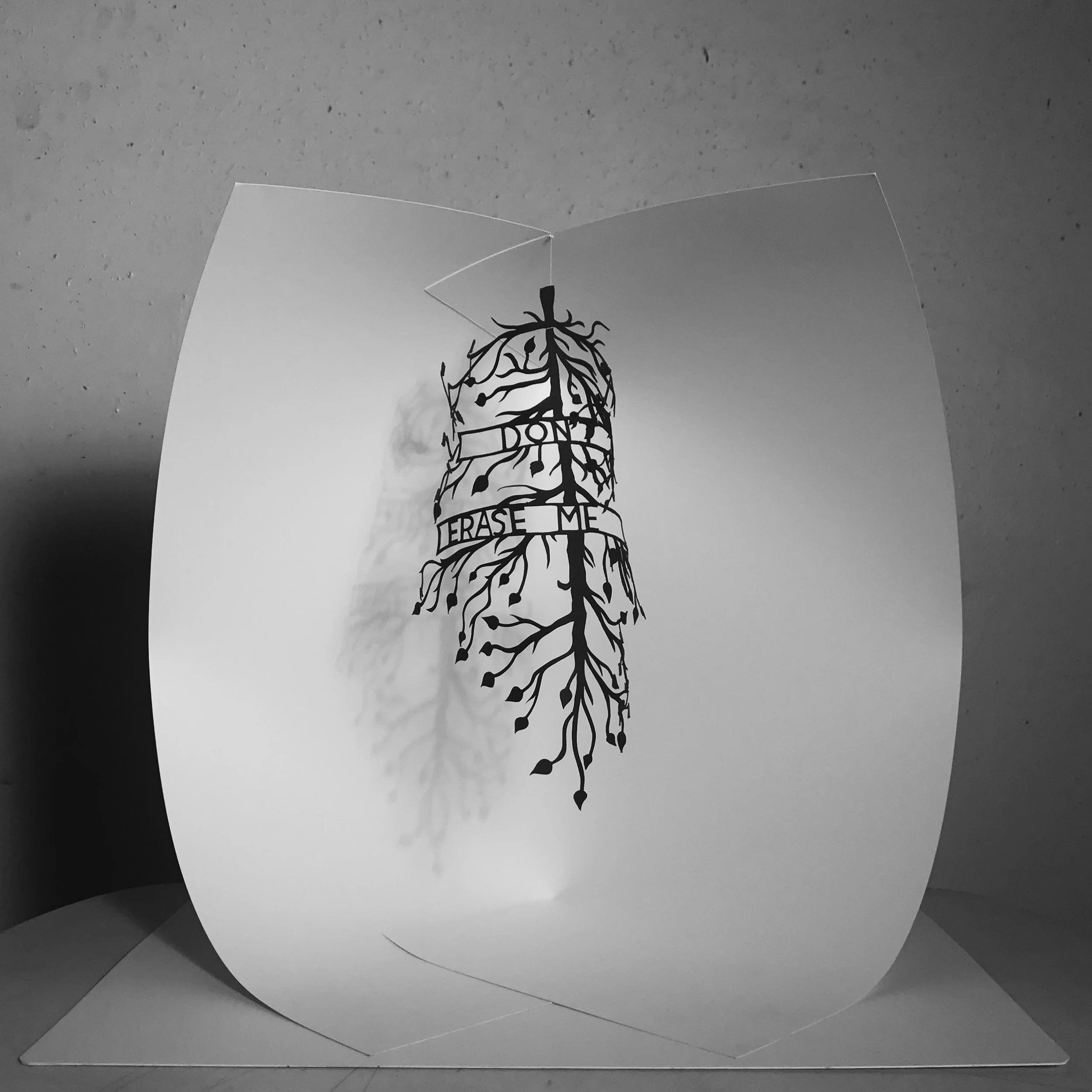

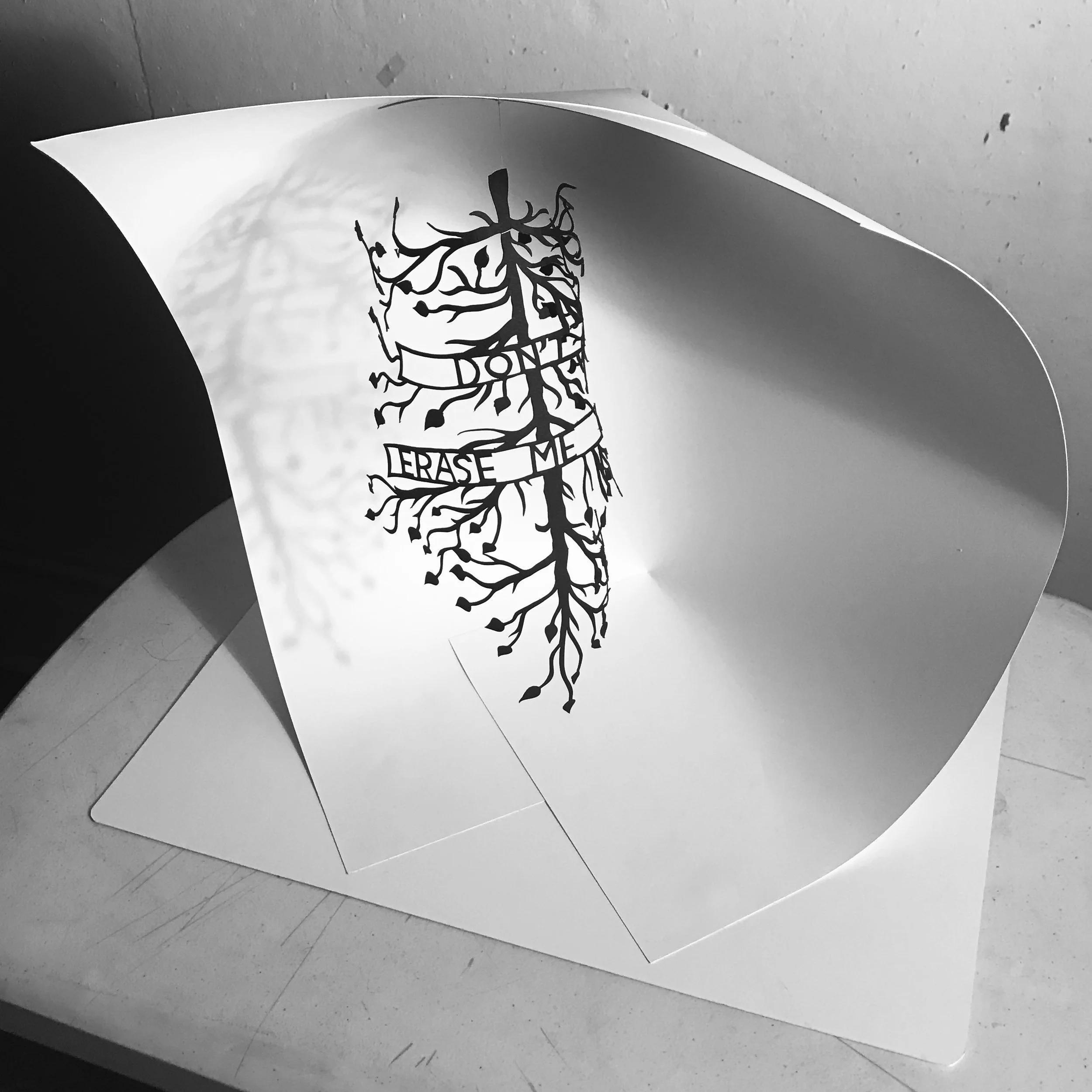

Bristol board, card stock. 13" x 20".

Don't Erase Me

Elizabeth Gilbert once said that the definition of an artist is anyone who walks through life saying “don’t erase me.” And perhaps no one says that louder than those of us with ink beneath our skin.

The earliest evidence of tattoos was found among the ruins of Ancient Egypt, but historians are sure the practice began even before then. The cultural significance varies widely; A tattoo can indicate the owner is of a specific trade or in a particular group. Many cultures believed that a tattoo of a majestic animal would imbue the wearer with the strength of that creature.

Tattoos eventually evolved into a form of storytelling. In the 1920s, Coney Island became a hub for tattooists, who found enthusiastic and willing customers in the nearby naval base. These traditional designs signified travel and experience. The swallow was a symbol of returning home. The anchor was a reminder of the wearer’s purpose in life.

But among the many beautiful uses for tattoos also rests a dark history. Throughout the Holocaust, the Nazis branded victims with serial numbers in order to organize and dispose of them. This practice gave the few prisoners who were eventually liberated a souvenir they never wanted.

The stigma around tattoos still runs deep, especially in the small Jewish community that I’m from. When my family fought for access to this country as refugees, the numbers on their arms stood as a constant reminder of what they'd seen. Somewhat ironically, it did what tattoos continue to do: isolated them from their peers.

Tattoos will always act as a form of division. The choice to mark my body will forever bar me from certain spaces. And although I love this medium regardless, there is a rebellious element that is undeniably appealing. Tattoos are taboo. Growing up, they were mysterious and dangerous and wrong. And I know that when my mother balks at every new addition to my arm, it is not simply a eulogy for my untainted skin: it is her feeling a rejection of everything she taught me.

However, there’s a group working to reclaim the art form for the beauty and comfort it can provide. We fiddle with the intricacies of a design for months. We think about placement and symbolism. I sit my mother down and explain that I chose lilacs because they’re her favorite flower, and these words because they motivate me, and this day because I may not get another.

These markings do what all art does. It allows the creator to say with some semblance of confidence: I exist. I was here. And that is enough.

“Tattoos are a permanent reminder of a temporary feeling,” my father once told me with disdain.

“Yes,” I thought.